The Holy Spirit

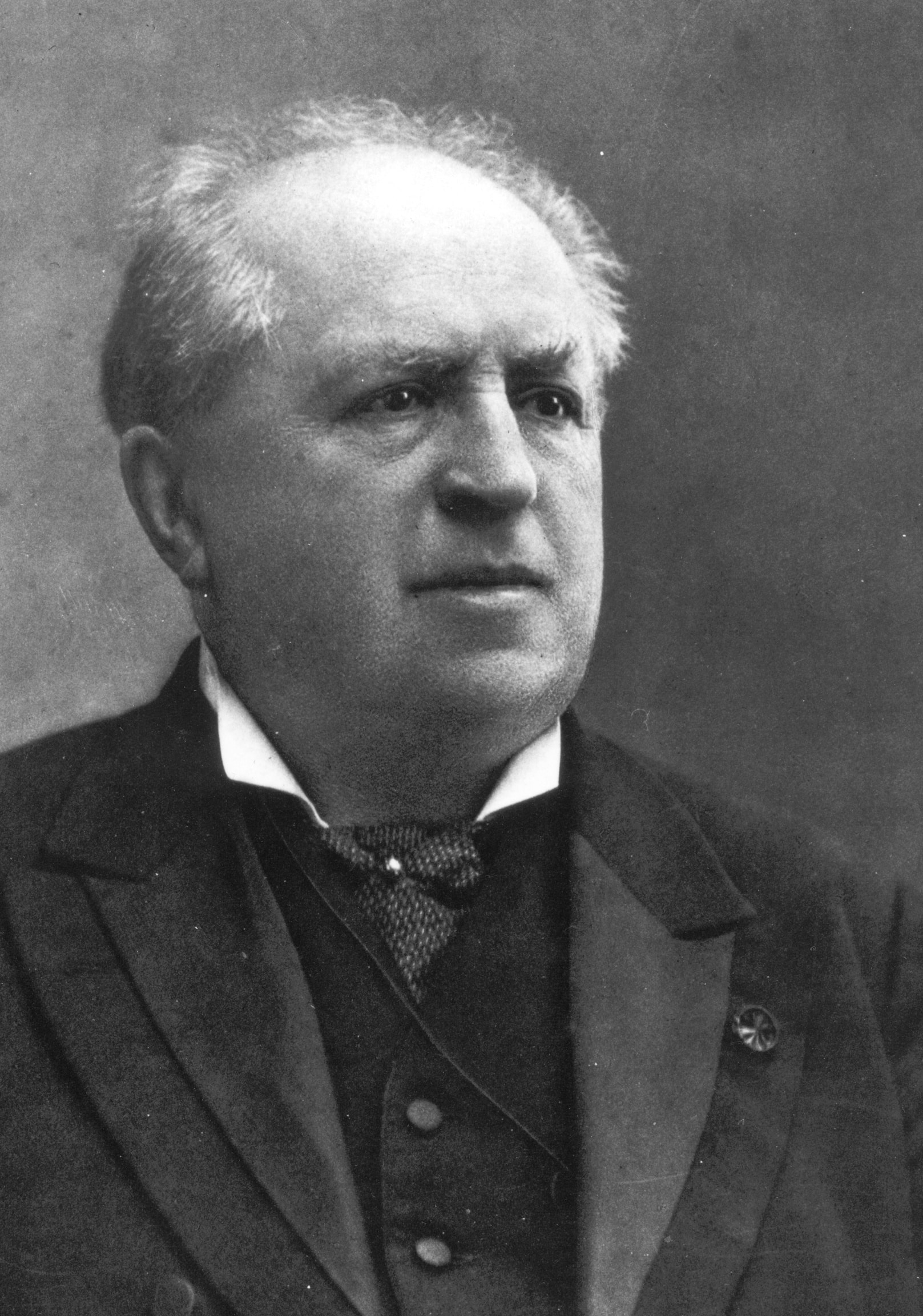

The Work of the Holy Spirit by Abraham Kuyper

The need of divine guidance is never more deeply felt than when one undertakes to give instruction in the work of the Holy Spirit—so unspeakably tender is the subject, touching the inmost secrets of God and the soul’s deepest mysteries.

We shield instinctively the intimacies of kindred and friends from intrusive observation, and nothing hurts the sensitive heart more than the rude exposure of that which should not be unveiled, being beautiful only in the retirement of the home circle. Greater delicacy befits our approach to the holy mystery of our soul’s intimacy with the living God. Indeed, we can scarcely find words to express it, for it touches a domain far below the social life where language is formed and usage determines the meaning of words.

Glimpses of this life have been revealed, but the greater part has been withheld. It is like the life of Him who did not cry, nor lift up nor cause His voice to be heard in the street. And that which was heard was whispered rather than spoken—a soul-breath, soft but voiceless, or rather a radiating of the soul’s own blessed warmth. Sometimes the stillness has been broken by a cry or a raptured shout; but there has been mainly a silent working, a ministering of stern rebuke or of sweet comfort by that wonderful Being in the Holy Trinity whom with stammering tongue we adore as the Holy Spirit.

Spiritual experience can furnish no basis for instruction; for such experience rests on that which took place in our own soul. Certainly this has value, influence, voice in the matter. But what guarantees correctness and fidelity in interpreting such experience? And again, how can we distinguish its various sources—from ourselves, from without, or from the Holy Spirit? The twofold question will ever hold: Is our experience shared by others, and may it not be vitiated by what is in us sinful and spiritually abnormal?

Altho there is no subject in whose treatment the soul inclines more to draw upon its own experience, there is none that demands more that our sole source of knowledge be the Word given us by the Holy Spirit. After that, human experience may be heard, attesting what the lips have confessed; even affording glimpses into the Spirit’s blessed mysteries, which are unspeakable and of which the Scripture therefore does not speak. But this can not be the ground of instruction to others.

The Church of Christ assuredly presents abundant spiritual utterance in hymn and spiritual song; in homilies hortatory and consoling; in sober confession or outbursts of souls wellnigh overwhelmed by the floods of persecution and martyrdom. But even this can not be the foundation of knowledge concerning the work of the Holy Spirit.

The following reasons will make this apparent:

First, The difficulty of discriminating between the men and women whose experience we consider pure and healthy, and those whose testimony we put aside as strained and unhealthful. Luther frequently spoke of his experience, and so did Caspar Schwenkfeld, the dangerous fanatic. But what is our warrant for approving the utterances of the great Reformer and warning against those of the Silesian nobleman? For evidently the testimony of the two men can not be equally true. Luther condemned as a lie what Schwenkfeld commended as a highly spiritual attainment.

Second, The testimony of believers presents only the dim outlines of the work of the Holy Spirit. Their voices are faint as coming from an unknown realm, and their broken speech is intelligible only when we, initiated by the Holy Spirit, can interpret it from our own experience. Otherwise we hear, but fail to understand; we listen, but receive no information. Only he that hath ears can hear what the Spirit has spoken secretly to these children of God.

Third, Among those Christian heroes whose testimony we receive, some speak clearly, truthfully, forcibly, others confusedly as tho they were groping in the dark. Whence the difference? Closer examination shows that the former have borrowed all their speech from the Word of God, while the others tried to add to it something novel that promised to be great, but proved only bubbles, quickly dissolved, leaving no trace.

Last, When, on the other hand, in this treasury of Christian testimony we find some truth better developed, more clearly expressed, more aptly illustrated than in Scripture; or, in other words, when the ore of the Sacred Scripture has been melted in the crucible of the mortal anguish of the Church of God, and cast into more permanent forms, then we always discover in such forms certain fixed types. Spiritual life expresses itself otherwise among the earnest-souled Lapps and Finns than among the light-hearted French. The ragged Scotchman pours out his overflowing heart in a different way from that of the emotional German.

Yea, more striking still, some preacher has obtained a marked influence upon the souls of men of a certain locality; an exhorter has got hold of the hearts of the people; or some mother in Israel has sent forth her word among her neighbors; and what do we discover? That in that whole region we meet no other expressions of spiritual life than those coined by that preacher, that exhorter, that mother in Israel. This shows that the language, the very words and forms in which the soul expresses itself, are largely borrowed, and spring but rarely from one’s own spiritual consciousness; and so do not insure the correctness of their interpretation of the soul’s experience.

And when such heroes as Augustine, Thomas, Luther, Calvin, and others present us something strikingly original, then we encounter difficulty in understanding their strong and vigorous testimony. For the individuality of these choice vessels is so marked that, unless sifted and tested, we can not fully comprehend them.

All this shows that the supply of knowledge concerning the work of the Holy Spirit, which, judging superficially, was to gush forth from the deep wells of Christian experience, yields but a few drops.

Hence for the knowledge of the subject we must return to that wondrous Word of God which as a mystery of mysteries lies still uncomprehended in the Church, seemingly dead as a stone, but a stone that strikes fire. Who has not seen its scintillating sparks? Where is the child of God whose heart has not been kindled by the fire of that Word?

But Scripture sheds scant light on the work of the Holy Spirit. For proof, see how much the Old Testament says of the Messiah and how comparatively little of the Holy Spirit. The little circle of saints, Mary, Simeon, Anna, John, who, standing in the vestibule of the New Testament, could scan the horizon of the Old Testament revelation with a glance—how much they knew of the Person of the Promised Deliverer, and how little of the Holy Spirit! Even including all the New Testament teachings, how scanty is the light upon the work of the Holy Spirit compared with that upon the work of Christ!

And this is quite natural, and could not be otherwise, for Christ is the Word made Flesh, having visible, well-defined form, in which we recognize our own, that of a man, whose outlines follow the direction of our own being. Christ can be seen and heard; once men’s hands could even handle the Word of Life. But the Holy Spirit is entirely different. Of Him nothing appears in visible form; He never steps out from the intangible void. Hovering, undefined, incomprehensible, He remains a mystery. He is as the wind! We hear its sound, but can not tell whence it cometh and whither it goeth. Eye can not see Him, ear can not hear Him, much less the hand handle Him. There are, indeed, symbolic signs and appearances: a dove, tongues of fire, the sound of a rushing, mighty wind, a breathing from the holy lips of Jesus, a laying on of hands, a speaking with foreign tongues. But of all this nothing remains; nothing lingers behind, not even the trace of a footprint. And after the signs have disappeared, His being remains just as puzzling, mysterious, and distant as ever. So almost all the divine instruction concerning the Holy Spirit is likewise obscure, intelligible only so far as He makes it clear to the eye of the favored soul.

We know that the same may be said of Christ’s work, whose real import is apprehended solely by the spiritually enlightened, who behold the eternal wonders of the Cross. And yet what wonderful fascination is there even for a little child in the story of the manger in Bethlehem, of the Transfiguration, of Gabbatha and Golgotha. How easily can we interest him by telling of the heavenly Father who numbereth the hairs of his head, arrayeth the lilies of the field, feedeth the sparrows on the house-top. But is it possible so to engage his attention for the Person of the Holy Spirit? The same is true of the unregenerate: they are not unwilling to speak of the heavenly Father; many speak feelingly of the Manger and of the Cross. But do they ever speak of the Holy Spirit? They can not; the subject has no hold upon them. The Spirit of God is so holily sensitive that naturally He withdraws from the irreverent gaze of the uninitiated.

Christ has fully revealed Himself. It was the love and divine compassion of the Son. But the Holy Spirit has not done so. It is His saving faithfulness to meet us only in the secret place of His love.

This causes another difficulty. Because of His unrevealed character the Church has taught and studied the Spirit’s work much less than Christ’s, and has attained much; less clearness in its theological discussion. We might say, since He gave the Word and illuminated the Church, He spoke much more of the Father and the Son than of Himself; not as tho it had been selfish to speak more of Himself—for sinful selfishness is inconceivable in regard to Him—but He must reveal the Father and the Son before He could lead us into the more intimate fellowship with Himself.

This is the reason that there is so little preaching on the subject; that text-books on Systematic Theology rarely treat it separately; that Pentecost (the feast of the Holy Spirit) appeals to the churches and animates them much less than Christmas or Easter; that unhappily many ministers, otherwise faithful, advance many erroneous views upon this subject—a fact of which they and the churches seem unconscious.

Hence special discussion of the theme deserves attention.

That it requires great caution and delicate treatment need not be said. It is our prayer that the discussion may evince such great care and caution as is required, and that our Christian readers may receive our feeble efforts with that love which suffereth long.

Abraham Kuyper, The Work of the Holy Spirit (New York; London: Funk & Wagnalls, 1900), 3–7.