Theology Proper

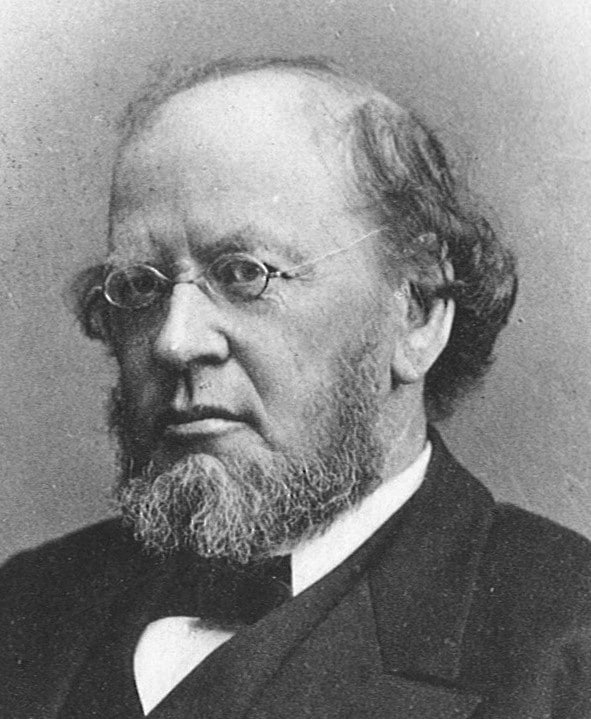

The Infinite Power of God by A. A. Hodge

46. What is meant by the omnipotence of God?

Power is that efficiency which, by an essential law of thought, we recognize as inherent in a cause in relation to its effect. God is the uncaused first cause, and the causal efficiency of his will is absolutely unlimited by any thing outside of the divine perfections themselves.

47. What distinction has been marked between the Potestas absoluta, and the Potestas ordinata of God?

The Scriptures and right reason teach us that the causal efficiency of God is not confined to the universe of second-causes and their active properties and laws. The phrase Potestas absoluta expresses the omnipotence of God absolutely considered in himself—and specifically that infinite reserve of power which remains with him, as a free personal attribute, above and beyond all the powers of nature and his ordinary providential actings upon and through them. Creation, miracles, etc, are exercises of this power of God. The Potestas ordinata on the other hand is the power of God as it is now exercised in and through the established system of second causes, in the ordinary course of Providence. Rationalists and advocates of mere naturalism, who deny miracles, and any form of divine interference with the established order of nature, of course admit only the latter and deny the former mode of divine power.

Archibald Alexander Hodge, Outlines of Theology: Rewritten and Enlarged (New York: Hodder & Stoughton, 1878), 149.

48. In what sense is the power of God limited and in what sense is it unlimited?

We are conscious with respect to our own causal efficiency. 1st That it is very limited. We have direct control only over the course of our thoughts, and the contractions of a few muscles. 2d. That we depend upon the use of means to produce the effects we design. 3d. We are dependent upon outward circumstances which limit and condition us continually.

The power inherent in the divine will on the other hand can produce whatever effects he intends immediately, and when he condescends to use means he freely endows them with whatever efficiency they possess. All outward circumstances of every kind are his own creation, conditioned upon his will, and therefore incapable of limiting him in any way. He is absolutely unlimited in the exercise of his power. He can not do wrong, nor work contradictions, because his power is the causal efficiency of an infinitely rational and righteous essence. His power therefore is limited only by his own perfections.

49. Is the distinction in us between power and will a perfection or a defect, and does it exist in God?

It is objected that if our power was equal to our design, and every volition resulted immediately in act, we would not be conscious of the difference between power and will. We admit that when a man’s power fails to be commensurate with his will it is a defect—and that this never is the case with God. But on the other hand when a man is conscious that he possesses powers which he might but does not will to exercise, he is conscious that it is an excellence—and that his nature is the more perfect for the possession of such reserves of power than it would otherwise be. To hold that there is nothing in God which is not in actual exercise, that his power extends no further than his will, is to make him no greater than his finite creation. The actions of a great man impress us chiefly as the exponents of vastly greater power which remains in reserve. So it is with God.

50. How can absolute omnipotence be proved to belong to God?

1st. It is asserted by Scripture.—Jer. 32:17; Matt. 19:26; Luke 1:37; Rev. 19:6.

2d. It is necessarily involved in the very idea of God as an infinite being.

3d. Although we have seen but part of his ways (Job 26:14), yet our constantly extending experience is ever revealing to us new and more astonishing evidences of his power, which always indicate an inexhaustible reserve.

Archibald Alexander Hodge, Outlines of Theology: Rewritten and Enlarged (New York: Hodder & Stoughton, 1878), 149–150.