One of the most obvious symbolism that stands out to us religious Jews is the fact that the mikvah– the ritual immersion pool, holds forty measured seah of water. For ritual purity Jews immerse themselves fully in a ritual bath filled with mayim chayim – living waters, or natural flowing water. A person dips into the pool fully nude and immerses themselves completely in order to purify themselves. When one does this they become like a new-born person, being surrounded on all sides in a pool of natural water one emerges pure like the day they were born.

Steps to an ancient Israeli mikvah. Though any natural pool of water can be used, the mikvah is specially made to provide the spiritual space to ritually dip even when a natural body of water like an ocean or lake is not nearby. Diverted and filtered rainwater and snow are used to fill it.

For this reason it is the common custom for newly religious Jews and converts to immerse in a mikvah. To symbolize their rebirth and emergence as a new and whole person.

Mikvah is a big deal in our tradition. It is something essential for religious Jews, immersing before taking upon ourselves special religious duties; this ritual takes us back to the temple period where the priest immersed themselves. Many orthodox Jews immerse before shabbat or high holidays. Others that are more mystical such as chassidim immerse themselves in a mikvah everyday before praying in the morning.

Of course today most primarily consider the mikvah as an essential for taharat hamisphacha – family purity. Men and women immerse themselves in preparation for their coming together in marriage. Women purify themselves after every menstruation and child-birth before becoming intimate again.

The above caption and picture taken from: https://hardcoremesorah.wordpress.com/tag/mikveh/

By the time of Christ, ceremonial cleanliness by water had become institutionalized into a purity ritual involving full immersion in a mikveh (or miqveh), a “collection of water.”

A recently discovered ancient mikveh in Israel

Mikveh purification was required of all Jews before they could enter the Temple or participate in major festivals. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims converged on Jerusalem for Passover and other major feasts. One hundred mikvehs, attesting to the need for water purification before entering into Temple rites, have been found by Hebrew University’s Benjamin Mazar around the wall adjacent to Herod’s Temple. Mikvehs, resembling large bathtubs or small garden ponds, have been found in Jericho and elsewhere in Israel.

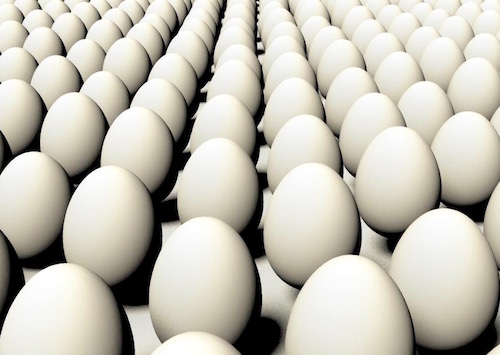

The ancient Jews tried to make sure their family’s mikveh was connected to a source of “living water” like a spring or well, but that was not always possible. Tap water could not be used as the primary source of water for the mikveh, but the rabbis decided you could “top off” the mikveh to a suitable level with a little tap water. The rule of thumb was that the mikveh should be big enough to hold 40 seahs of water. When asked how much volume a seah was, the rabbis said it was enough to fit 144 eggs. If there were less than 40 seahs of water (enough to hold 5,760 eggs) in a mikveh, you could not add even 3-4 more pints of water from an unnatural source because that would render the mikveh unfit for use. It would have to be drained and refilled.

If there were less than 40 seahs of water (enough to hold 5,760 eggs) in a mikveh, you could not add even 3-4 more pints of water from an unnatural source because that would render the mikveh unfit for use. It would have to be drained and refilled.

The above caption and picture taken from:https://earlychurchhistory.org/medicine/ancient-jews-cleanliness/

http://messianicpublications.com/ariel-ben-lyman-hanaviy/tevilah-and-mikveh/

http://jesus-messiah.com/html/mikveh.html

John Lightfoot writes about John the Baptist:

III. The baptism of proselytes was an obligation to perform the law; that of John was an obligation to repentance. For although proselytical baptism admitted of some ends,—and circumcision of others,—yet a traditional and erroneous doctrine at that time had joined this to both, that the proselyte covenanted in both, and obliged himself to perform the law; to which that of the apostle relates, Gal. 5:3, “I testify again to every man that is circumcised, that he is a debtor to do the whole law.”

But the baptism of John was a ‘baptism of repentance;’ Mark 1:4: which being undertaken, they who were baptized professed to renounce their own legal righteousness; and, on the contrary, acknowledged themselves to be obliged to repentance and faith in the Messias to come. How much the Pharisaical doctrine of justification differed from the evangelical, so much the obligation undertaken in the baptism of proselytes differed from the obligation undertaken in the baptism of John: which obligation also holds amongst Christians to the end of the world.

IV. That the baptism of John was by plunging the body (after the same manner as the washing of unclean persons, and the baptism of proselytes was), seems to appear from those things which are related of him; namely, that he “baptized in Jordan;” that he baptized “in Ænon, because there was much water there;” and that Christ, being baptized, “came up out of the water:” to which that seems to be parallel, Acts 8:38, “Philip and the eunuch went down into the water,” &c. Some complain, that this rite is not retained in the Christian church, as though it something derogated from the truth of baptism; or as though it were to be called an innovation, when the sprinkling of water is used instead of plunging. This is no place to dispute of these things. Let us return these three things only for a present answer:—

1. That the notion of washing in John’s baptism differs from ours, in that be baptized none who were not brought over from one religion, and that an irreligious one too,—into another, and that a true one. But there is no place for this among us who are born Christians: the condition, therefore, being varied, the rite is not only lawfully, but deservedly, varied also. Our baptism argues defilement, indeed, and uncleanness; and demonstrates this doctrinally,—that we, being polluted, have need of washing: but this is to be understood of our natural and sinful stain, to be washed away by the blood of Christ and the grace of God: with which stain, indeed, they were defiled who were baptized by John. But to denote this washing by a sacramental sign, the sprinkling of water is as sufficient as the dipping into water,—when, in truth, this argues washing and purification as well as that. But those who were baptized by John were blemished with another stain, and that an outward one, and after a manner visible; that is, a polluted religion,—namely, Judaism, or heathenism; from which, if, according to the custom of the nation, they passed by a deeper and severer washing,—they neither underwent it without reason; nor with any reason may it be laid upon us, whose condition is different from theirs.

2. Since dipping was a rite used only in the Jewish nation and proper to it, it were something hard, if all nations should be subjected under it; but especially, when it is neither necessarily to be esteemed of the essence of baptism, and is moreover so harsh and dangerous, that, in regard of these things, it scarcely gave place to circumcision. We read that some, leavened with Judaism to the highest degree, yet wished that dipping in purification might be taken away, because it was accompanied with so much severity. “In the days of R. Joshua Ben Levi, some endeavoured to abolish this dipping, for the sake of the women of Galilee; because, by reason of the cold, they became barren. R. Joshua Ben Levi said unto them, Do ye go about to take away that which hedges in Israel from transgression?” Surely it is hard to lay this yoke upon the neck of all nations, which seemed too rough to the Jews themselves, and not to be borne by them, men too much given to such kind of severer rites. And if it be demanded of them who went about to take away that dipping, Would you have no purification at all by water? it is probable that they would have allowed of the sprinkling of water, which is less harsh, and not less agreeable to the thing itself.

3. The following ages, with good reason, and by divine prescript, administered a baptism differing in a greater matter from the baptism of John; and therefore it was less to differ in a less matter. The application of water was necessarily of the essence of baptism; but the application of it in this or that manner speaks but a circumstance: the adding also of the word was of the nature of a sacrament; but the changing of the word into this or that form, would you not call this a circumstance also? And yet we read the form of baptism so changed, that you may observe it to have been threefold in the history of the New Testament.

Secondly, In reference to the form of John’s baptism [which thing we have propounded to consider in the second place], it is not at all to be doubted but he baptized “in the name of the Messias now ready to come:” and it may be gathered from his words, and from his story. As yet he knew not that Jesus of Nazareth was the Messias: which he confesseth himself, John 1:31: yet he knew well enough, that the Messias was coming; therefore, he baptized those that came to him in his name, instructing them in the doctrine of the gospel, concerning faith in the Messias, and repentance; that they might be the readier to receive the Messias when he should manifest himself. Consider well Mal. 3:1, Luke 1:17, John 1:7, 31, &c. The apostles, baptizing the Jews, baptized them “in the name of Jesus;” because Jesus of Nazareth had now been revealed for the Messias; and that they did, when it had been before commanded them by Christ, “Baptize all nations in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.” So you must understand that which is spoken, John 3:23, 4:2, concerning the disciples of Christ baptizing; namely, that they baptized in ‘the name of Jesus,’ that thence it might be known that Jesus of Nazareth was the Messias, in the name of whom, suddenly to come, John had baptized. That of St. Peter is plain, Acts 2:38; “Be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ:” and that, Acts 8:16, “They were baptized in the name of Jesus.”

But the apostles baptized the Gentiles, according to the precept of our Lord, “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost,” Matt, 28:19

John Lightfoot, A Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica, Matthew-1 Corinthians, Matthew-Mark, vol. 2 (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2010), 63–66.

Scripture references relating to washings:

https://www.biblegateway.com/resources/dictionary-of-bible-themes/7426-ritual-washing

History and Archaeology

During the Second Temple period (roughly from 100 B.C.E. to 70 C.E.), the Jewish population in Palestine had a very distinctive practice of purification within water installations known as mikva’ot. Large numbers of stepped-and-plastered mikva’ot have been found in excavations in Jerusalem, in outlying villages, as well as at various rural locations. Most of the installations in Jerusalem were in basements of private dwellings and therefore must have served the specific domestic needs of the city inhabitants. Numerous examples are known from the area of the “Upper City” of Second Temple period Jerusalem (the present-day Jewish Quarter and Mount Zion), with smaller numbers in the “City of David” and the “Bezetha Hill.” A few slightly larger mikva’ot are known in the immediate area of the Temple Mount, but these installations could not have met the needs of tens of thousands of Jewish pilgrims from outside the city attending the festivities at the Temple on an annual basis. It would appear that the Bethesda and Siloam Pools – to the north and south of the Temple Mount – were designed at the time of Herod the Great to accommodate almost all of the ritual purification needs of the large numbers of Jewish pilgrims who flocked to Jerusalem for the festivals. In addition to this, those precluded from admission to the Temple, owing to disabilities and bodily defects, would have sought miraculous healing at these pools and this is the background for the healing accounts in the Gospel of John (5: 1–13; 9: 7, 11).

Although water purification is referred to in the Old Testament, in regard to rituals and the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, with washing, sprinkling, and dipping in water, we do not hear of specific places or installations that people would constantly frequent for the purpose of ritually cleansing their flesh. The term mikveh was used in a very general sense in the Old Testament to refer to a body of water of indeterminate extent (cf. Gen. 1:10; Ex. 7:19), or more specifically to waters gathered from a spring or within a cistern (Lev. 11: 36) or waters designated for a large reservoir situated in Jerusalem (Isa. 22: 11). None of these places are mentioned as having been used for ritual purification in any way. Hence, the concept of the mikveh as a hewn cave or constructed purification pool attached to one’s dwelling or place of work is undoubtedly a later one. A distinction must be made therefore between the purification practices as they are represented in biblical sources, with Jewish water immersion rituals of the Second Temple period, as well as with later customs of mikva’ot prevailing from medieval times and to the present day (see below).

The basis for our information about what was or was not permitted in regard to mikva’ot appears in rabbinic sources: the tractate Mikva’ot in the Mishnah and Tosefta. One must take into consideration, however, that this information might very well be idealized, at least in part, and that the reality of purification practices in Second Temple times may have been much more flexible than one would suppose from these sources. Josephus Flavius is silent in his writings about the purification installations of his time, and the few references in Dead Sea Scroll manuscripts are definitely not to be relied upon to generalize about the common Jewish purification practices current in Second Temple period Palestine. The Mishnah (Mik. 1:1–8, ed. Danby) indicates that there were at least six grades of mikva’ot, listed from the worst to the best: (1) ponds; (2) ponds during the rainy season; (3) immersion pools containing more than 40 se’ahof water; (4) wells with natural groundwater; (5) salty water from the sea and hot springs; and (6) natural flowing “living” waters from springs and in rivers. Clearly the ubiquitous stepped-and-plastered installation known to scholars from archaeological excavations since the 1960s and now commonly referred to as the mikveh (referred to under No. 3, above) was not the best or the worst of the six grades of mikva’ot as set forth in the Mishnah. It is referred to as follows: “More excellent is a pool of water containing forty se’ah; for in them men may immerse themselves and immerse other things [e.g., vessels]” (Mik. 1:7). The validity of mikva’ot was apparently one of the subjects occasionally debated in the “Chamber of Hewn Stone” in Jerusalem (Ed. 7:4).

Stringent religious regulations (halakhot) are referred to in regard to certain constructional details and how the installations were to be used. A mikveh had to be supplied with “pure” water derived from natural sources (rivers, springs or rain) throughout the year and even during the long dry season, and it had to contain a minimum of 40 se’ah of water (the equivalent of less than one cubic meter of water) so that a person might be properly immersed (if not standing, then lying down). Once the natural flow of water into a mikveh had been stopped, it became “drawn” water (mayim she’uvim). Water could not be added mechanically, but there was a possibility of increasing the volume by allowing drawn water to enter from an adjacent container, according to the sources, so long as the original amount of water did not decrease to below the minimum requirement of water. Hence, an additional body of water, known since medieval times as the oẓar (the “treasury”), could be connected to the mikveh, and linked by pipe or channel. There was, of course, the problem of the water becoming dirty or stagnant (though not impure), but the mikveh was not used for daily ablutions for the purpose of keeping clean. Indeed, people appear to have washed themselves (or parts of their bodies, notably the feet and hands) before entering the ritual bath (Mik. 9:2). Basins for cleansing feet and legs have been found in front of the mikva’ot of Herodian dwellings in Jerusalem.

The mikveh was required, according to the rabbinical sources, to be sunk into the ground, either through construction or by the process of hewing into the rock, and into it natural water would flow derived from a spring or from surface rainwater in the winter seasons. There was, of course, the problem of silting (Mik. 2:6). The phenomenon of silts gathering within a mikveh was referred to quite clearly in rabbinic texts. For instance, in reference to the minimum quantity of water required in a mikveh for it to be ritually permissible, we hear that: “if the mud was scraped up [from the pool and heaped] by the sides, and three logs [a measure] of water drained down therein, it remains valid [for cleansing purposes]; but if the mud was removed away [from the pool] and three logs rained down therefrom [into the pool] it becomes invalid” (Mik. 2:6). Elsewhere, we are told about certain damming operations made inside the mikveh: “if the water of an immersion pool was too shallow it may be dammed [to one side] even with bundles of sticks or reeds, that the level of water may be raised, and so he may go down and immerse himself ” (Mik. 7:7).

The walls and floors of the mikveh chambers were plastered (frequently made of slaked quicklime mixed with numerous charcoal inclusions); ceilings were either natural rock or barrel-vaulted with masonry. These installations are distinguished by flights of steps leading down into them and extending across the entire breadth of the chamber; such ubiquitous steps, however, were not referred to in the sources. The riser of the lowest step tended to be deeper than the rest of the steps, presumably to facilitate the immersion procedures when the level of water had dropped to a minimum. Some of these steps had a low raised (and plastered) partition which is thought to have separated the descending impure person (on the right) from the pure person leaving the mikveh (on the left). Similarly there were mikva’ot with double entrances and these may indicate that the activities carried out inside them resembled those undertaken in installations with the partitioned steps. This arrangement of steps and/or double entrances is known mainly from Jerusalem, but also from sites in the vicinity, as well in the Hebron Hills and at Qumran. The installations from Jerusalem and the Hebron Hills with the single partitions fit well the double lane theory, that it was constructed to facilitate the separation of the impure from the pure, but at Qumran, installations were found with three or more of these partitions, which is odd. According to one suggestion (Regev) maintaining the utmost in purity inside the mikveh, reflected by the addition of features such as the partitions, would have been a concern mainly for priests, but little support for this hypothesis has been forthcoming from the archaeological evidence itself. Indeed, Galor rightly points out that the partitions are at best symbolic rather than functional, and that in some of the installations at Qumran they were not even practical, providing in one installation a stepped lane which was only 6 in. (15 cm.) wide!

The mikveh was also used for the purifying of contaminated vessels (e.g. Mik. 2:9–10, 5:6, 6:1, 10:1; cf. Mark 7:4). It is not surprising, therefore, that in the excavation of mikva’ot at Jericho and Jerusalem, some were found to contain quantities of ceramic vessels. Alternatively, it is quite possible that such mikva’ot were intended specifically for the purpose of cleaning vessels and were never used for the immersion of people. At Jericho, in one mikveh, located in the northern sector of the main Hasmonean palace, hundreds of intact ceramic vessels (mainly bowls) of the first century B.C.E. were found in a silt layer on the floor of one installation. It is quite possible that these vessels were abandoned at one stage of the cleansing process because there was too much silt inside the installation, a phenomenon referred to in the Mishnah (see Mik. 2:10). A large concentration of pottery was also found trapped beneath a collapse of ashlars in the lower part of a mikveh, dating to the first century B.C.E., which was uncovered in the Jewish Quarter excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem. The concentration of pottery found there mainly consisted of an unspecified number of small bowls, mostly intact.

The date of the first appearance of stepped-and-plastered mikva’ot is a matter still debated by scholars, but the general consensus of opinion is that this occurred in the Late Hellenistic (Hasmonean) period, at some point during the end of the second century B.C.E. or very early in the first century B.C.E. One thing is certain: only a handful of mikva’ot are known from the time of the Hasmoneans, whereas by contrast large numbers of mikva’ot are known dating from the time of Herod the Great (late first century B.C.E.) and up to the destruction of Jerusalem (70 C.E.). This, therefore, led Berlin to conclude that the appearance of mikva’ot cannot predate the mid-first century B.C.E., but there is sufficient evidence at Jerusalem, Jericho, Gezer, and elsewhere to support an earlier date than that. What there can be no doubt about is that the floruit in the use of mikva’ot was in the first century C.E.

To sum up what we know about the use of the household mikveh in the first century based on the rabbinic texts and archaeological finds: the average size of the mikveh suggests that ritual bathing was ordinarily practiced individually (no more than one person would enter the installation at a time) and the location of mikva’ot within the basements of private dwellings suggests this purification was done regularly and whenever deemed necessary. The purpose of the immersion was to ritually cleanse the flesh of the contaminated person in pure water, but it may also have been undertaken within households before eating or as an aid to spirituality, before reading the Torah or praying. It was neither used for the cleansing of the soul nor for the redemption of sins (as with the purification procedures of John the Baptist), or any other rituals (except for the conversion of proselytes following their acceptance of the Torah and circumcision; Pes. 8:8). One assumes that disrobing took place before the immersion and that new garments were put on immediately afterwards. Ritual bathing could be conducted in the comfort of a person’s dwelling, but there were also more public mikva’ot such as those used by peasants and other workers (such as quarrymen, potters, and lime burners) who would cleanse themselves at various locations in the landscape. A few mikva’ot are known in the immediate vicinity of tombs, but they are quite rare indicating that ritual purification following entrance into tombs was not common. The mikveh was not used for general cleaning and ablution purposes: this was done in alternative installations located within the house, or in public bathhouses instead.

The fact that so many mikva’ot are known from greater Jerusalem, from within the city itself as well as from the villages and farms in its hinterland, is a very clear reflection of the preoccupation Jerusalemites had in the first century with the concept of separating and fixing the boundary between the pure and the impure. A general concern about purity was common to all Jews at that time and especially in the city that contained the House of God – the Jewish Temple. There are definitely no grounds for linking the phenomenon of mikva’ot in Jerusalem to any one specific group within Judaism, as some have done. In the eyes of the inhabitants of the city, a clear separation would have been made between the use of natural and built places for purification. While rabbinical sources may have extolled the higher sanctity of immersing in natural sources of water, the ease with which immersion could be made in a specifically designed installation situated in the basement of a house, made it far more convenient than having to set forth into the countryside in search of a natural source of water in which one might seek to purify oneself. Natural sources of water were either situated at a distance from the city (e.g., the Jordan River), or were difficult to access (e.g., a spring used for irrigation for agriculture), or were only available at the right season in the year (e.g., pools in rocky depressions that filled up after the winter rains). Above all, it would appear that convenience counted as the most important consideration when a mikveh came to be built in the first century. A stepped-and-plastered installation in the basement of a house satisfied all those who wished to immerse themselves on a regular basis for purification. To that end the installation had to have had a satisfactory incoming source of pure water, and in most instances rainwater sufficed. Everything else was done for reasons of fashion and personal preference, and one should include such things as footbaths outside the mikveh, double entrances, and lane partitions on the steps. The idea that the construction of mikva’ot was done in strict accordance and adherence to religious rules and stipulations (such as those debated in the “Chamber of Hewn Stone”; Ed. 7:4) is highly unlikely and finds no support in the archaeological evidence itself. Hence, the information about mikva’ot as it appears in the tractates of the Mishna and Tosefta should probably be regarded as representing a certain degree of rabbinical idealism rather than the complete reality of empirical practice of mikveh construction that was supposedly passed down through the generations following the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 C.E.

The important and obvious conclusion, however, is that the rise in the popularity of this installation during the first century C.E. no doubt reflects changing attitudes that were coming to the fore in regard to the perception of everyday purity and possible sources of ritual contamination. In a way, we may regard the later rabbinical writings on the subject of mikva’ot as the reflected culmination of a heightened process of Jewish awareness regarding purity that began to intensify particularly in the mid-first century C.E. An unprecedented number of mikva’ot ultimately came to be built, sometimes with more than one or two installations per household, and not just in the city of Jerusalem but in the outlying villages and farms as well. This development may also be paralleled with the sudden upsurge seen in the manufacturing of stone vessels in the mid-first century C.E. (from c. 50 C.E. or perhaps 60) onwards. Such vessels were perceived of as being able to maintain purity and as such were extremely popular in the “household Judaism” assemblage of that time (see Berlin 2005), with small mugs and large (kalal) jars serving a particularly useful task during hand-washing purification procedures. Perhaps we should regard mikva’ot and stone vessels as two sides of the same coin representing the overall “explosion” of purity that took place within Judaism in the first century C.E. (“purity broke out among the Jews”; Tosef. Shab. 1:14), stemming from changing religious sensibilities on the one hand and perhaps serving on the other as a form of passive Jewish resistance against encroaching features of Roman culture in the critical decade or so preceding the Great Revolt.

The above caption taken from: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/mikveh

Is The Mikvah Only Used By Women?

No, the mikvah is used for various things:

- It is the final stage of conversion to Judaism

- It is used by men customarily at auspicious times, such as before Yom Kippur and a groom on his wedding day. Many men use it Erev Shabbos, while some chassidic men even use the mikvah daily before prayer.

- Generally, new dishes should also be immersed in the mikvah before use.

Taken from: http://www.oxfordchabad.org/templates/articlecco_cdo/aid/566668/jewish/Mikvah-Facts.htm